Particle Filter Drone Navigation

Vision-based pose estimation and particle filter navigation for a nano-quadrotor

Overview

This project develops a computer vision–based pose estimation pipeline and a particle filter navigation system for a nano-quadrotor flying over an AprilTag mat.

The work is split into two tightly coupled parts: a perspective-n-point (PnP) observation model that estimates the drone pose from camera images, and a fifteen-state inertial navigation particle filter that fuses this pose with IMU data.

Drone Observation Model

This module implements a perspective-n-point (PnP) observation model that uses calibrated camera intrinsics and an AprilTag map to estimate the 6-DoF pose of the drone.

Each image provides AprilTag detections with pixel-space corner coordinates and IDs; these are paired with their known 3D world-frame locations to form 2D–3D correspondences for pose estimation.

AprilTag Map and Calibration

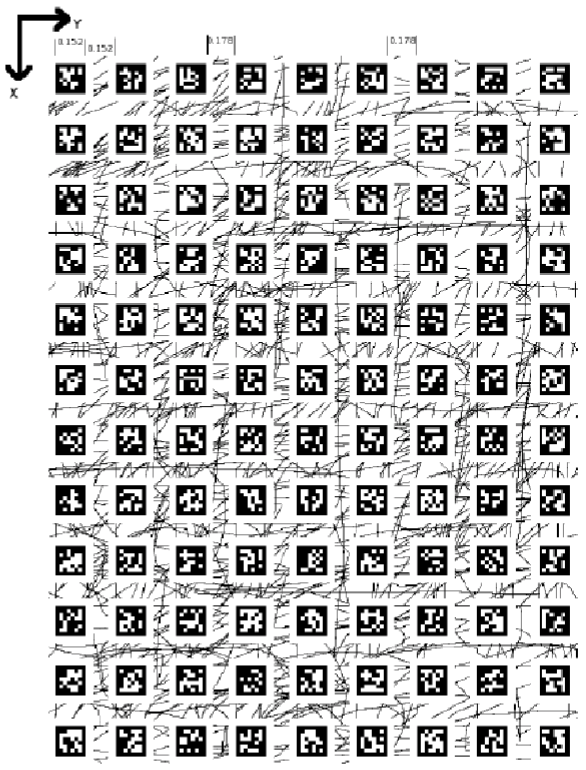

The AprilTags are arranged in a 12×9 grid with known tag size and spacing, allowing the 3D coordinates of every tag corner in the world frame to be computed analytically.

Camera intrinsics and radial/tangential distortion parameters are provided, and the estimated camera pose is transformed into the drone body frame using a fixed extrinsic transform.

PnP Pose Estimation

For each frame, the pipeline extracts corner points of all visible AprilTags and feeds their 2D–3D correspondences to a PnP solver (e.g., OpenCV’s solvePnP) to estimate camera position and orientation.

The resulting rotation matrix is converted to Euler angles (roll, pitch, yaw) using analytic expressions derived from the matrix structure to resolve angle ambiguities.

Trajectory Visualization

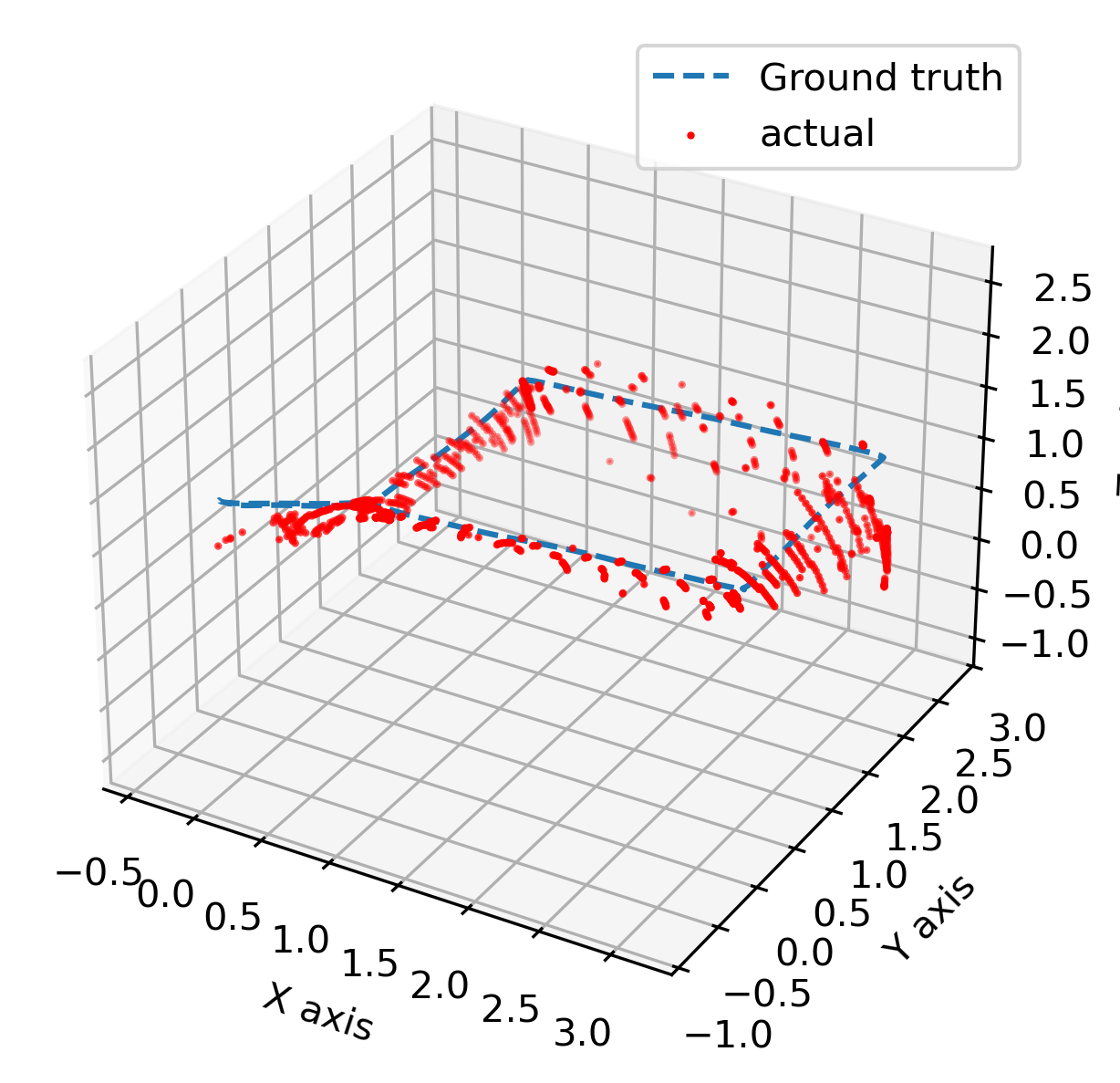

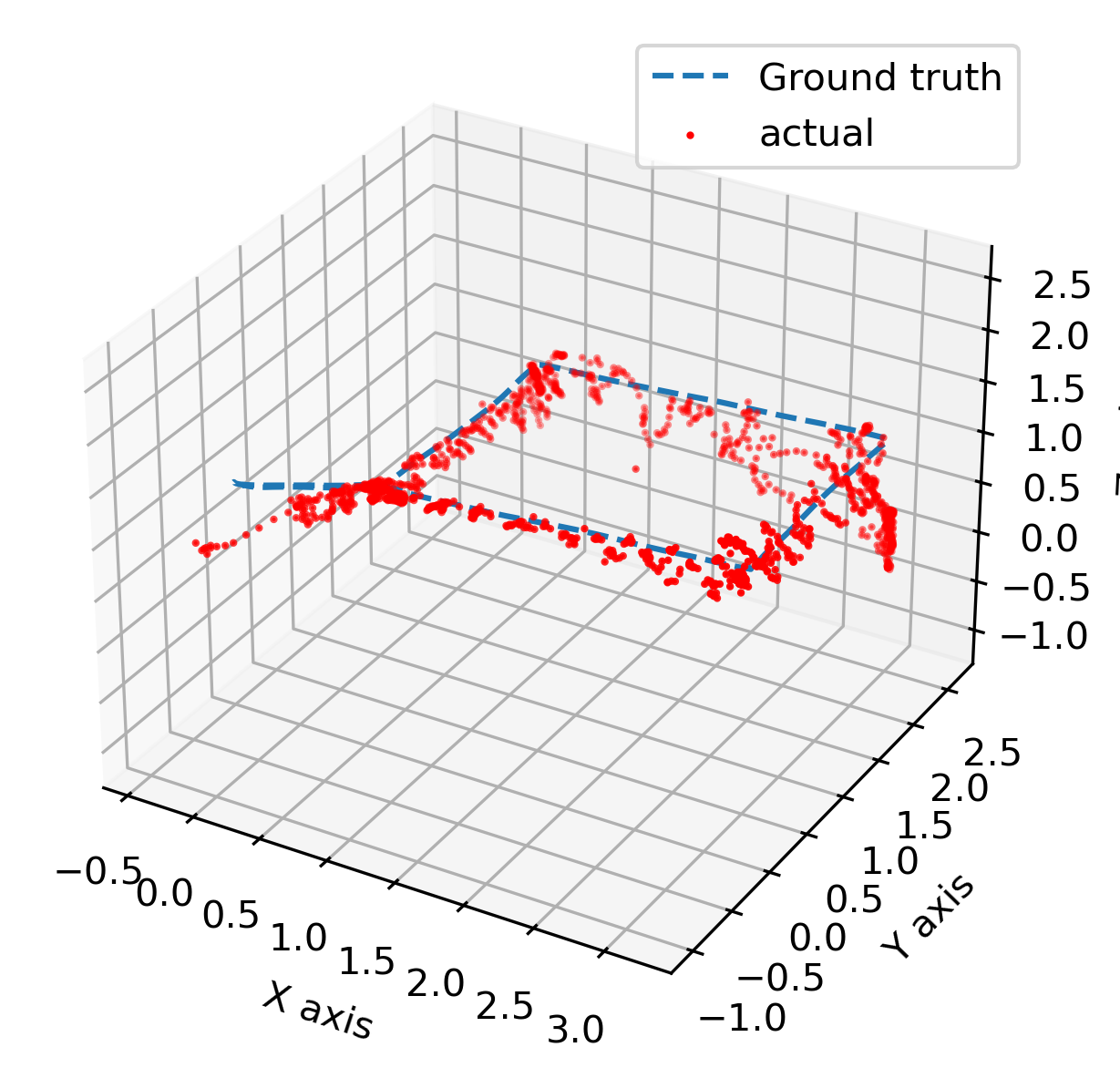

The estimated pose is computed for each time step and compared to motion-capture ground truth, producing 3D position plots and roll/pitch/yaw time histories.

These visualizations highlight how AprilTag visibility, viewing angle, and tag layout influence pose accuracy across the trajectory.

Covariance Estimation

To use the observation model inside a navigation filter, the measurement noise covariance is estimated from residuals between the PnP pose estimates and motion-capture ground truth.

Sample covariance over position and orientation residuals is computed and then adjusted into a practical covariance matrix (R) that captures realistic sensor noise while remaining numerically stable.

Particle Filter Navigation

The navigation component uses a fifteen-state inertial model driven by IMU measurements to propagate a set of particles representing possible drone states.

States include 3D position, 3D velocity, 3D attitude (Euler Z–X–Y), and accelerometer and gyroscope biases, allowing the filter to model both motion and slowly varying sensor errors.

Process Model and IMU Modeling

IMU outputs (angular velocity and linear acceleration) are modeled as noisy versions of the true body-frame motion, with additive white noise and bias random walks for both gyroscopes and accelerometers.

The process model uses these IMU signals, gravity, and the current attitude to propagate position, velocity, orientation, and bias states forward in time for each particle.

Vectorized Particle Propagation

To handle thousands of particles efficiently, the implementation stores all particles in an array and applies vectorized linear algebra operations for prediction and update.

This approach avoids Python-level loops, significantly reducing runtime and enabling experiments with particle counts from 250 up to 5000.

Measurement Update and Resampling

At measurement times, the AprilTag-based observation model provides a pose measurement and covariance, which are used to compute importance weights for each particle via the observation likelihood.

A low-variance resampling algorithm then draws a new particle set from the weighted distribution, focusing computational effort on high-probability regions and mitigating particle degeneracy.

Navigation Solution and Metrics

Because a particle filter represents the state distribution as a weighted set, the navigation solution is obtained using statistics such as maximum-weight particle, unweighted mean, or weighted mean over all particles.

For each choice, root-mean-square error (RMSE) versus ground truth is computed, enabling comparison of solution strategies and quantifying the effect of particle count on accuracy.

Analysis and Comparison

The project includes a comparison between the particle filter and a nonlinear Kalman filter from a related assignment, focusing on implementation effort, tuning difficulty, runtime, and tracking accuracy.

While both are nonlinear estimators, the particle filter offers greater flexibility for non-Gaussian and multimodal distributions but requires more computation and careful particle management.

Key Takeaways

The combined system demonstrates how a vision-based PnP observation model can be integrated with an IMU-driven particle filter to achieve robust drone navigation over a known fiducial map.

Experiments with different particle counts, covariance choices, and solution statistics provide insight into the trade-offs between accuracy, robustness, and computational cost in practical navigation systems.